ABSTRACT

This article1 analyzes the form of compositions in a tradition of instrumental performance for the two-stringed, long-necked lute dutar, the main instrument used in the traditional music played by Turkmens in Turkmenistan and northern Iran. While this instrumental tradition is perhaps ancillary to a more prominent vocal tradition surrounding the figure of the bagşy, a bard similar to the aşık or ashug in Azerbaijan and Turkey, musicians in parts of Turkmenistan have nonetheless developed a rich repertoire of instrumental compositions. I argue that within instrumental dutar compositions, there are no fixed, traditional compositional forms akin to those found in many other musical traditions. However, it is possible to identify what I call recurring formal strategies for organizing compositions. These include employing an arc-shaped countour in which the overall pitch of the piece ascends to a climax before descending downward again; the use of recurring motifs, especially in the cadential portions of otherwise differing sections of a piece; transposing melodic material upward; and building to an exciting climax by playing in a high range on the higher-pitched of the instrument’s two strings while the lower-pitched string drones open below it, for example. I highlight these formal strategies using three case studies of traditional pieces of uncertain or collective authorship: the pieces “Gonurbaş mukamy,” “Humar ala,” and “Döwletyar gyrk.” I offer recordings, partial transcriptions, and schematic analyses as needed to outline the form of these compositions and where and how particular formal strategies are employed. Because I draw on only three examples, I emphasize that my analysis reveals a non-exhaustive sample of such formal strategies. The formal strategies I identify neither appear in all pieces in the traditional repertoire nor do they represent all such formal strategies that a more extensive number of case studies might reveal. While the article is organized around my argument that the dutar masters who developed the traditional repertoire employed these formal strategies in order to craft and further develop traditional instrumental compositions, I also intend this article as a listening guide for readers unfamiliar with Turkmen music.

ÖZET

Bu makalede, Türkmenistan ve Kuzey İran’daki Türkmenlerin geleneksel müziğinin aslî sazı olan iki-telli, uzun-saplı “dutar” sazının icra geleneğindeki beste formları incelenmektedir. Bu saz icrası geleneği, Azerbaycan ve Türkiye’deki “âşık, ozan” olarak addedilen “bagşı” figürü etrafında şekillenmiş sözlü geleneğe nazaran daha arka planda kalmış olmakla birlikte oldukça zengin bir beste repertuvarına da sahiptir. Bu makalede, dutar sazının saz eseri bestelerinde, diğer müzikal geleneklerde benzerleri görülen sabit, değişmeyen, gelenekselleşmiş beste formlarının yer almadığı tezini savunacağım. Öte yandan, besteleme sürecinde, kendi tabirimle yinelenen biçimsel yöntemleri teşhis etmenin de mümkün olduğunu belirtmek isterim. Bestede pest perdeye inmeden önce tiz perdeye çıkılan kubbe şeklinde melodi çizgisi (arc-shaped contour); özellikle bir bestenin farklılık gösteren bölümlerinin karar (cadential) kısımlarında mükerrer nağme kullanımı; melodik materyalin yüksek perdeye transpozisyonu; ve dutarın iki telinden pest olanıyla zeminde dem sesi verilirken tiz olan teliyle tiz perdelerden çalarak melodiyi heyecan verici bir tiz perdeye çıkarmak bu yöntemlere örnektir. Mevzu bahis biçimsel yöntemleri vurgulamak için anonim veya müşterek kaynaklardan alınma “Goñurbaş mukamy,” “Humar ala,” ve “Döwletyar gyrk” adlı üç besteyi örnek alarak bu yöntemlerin incelemesini yapacağım. İncelemeleri yaparken bu bestelerin formlarını, hangi hususi biçimsel yöntemlerin ne zaman ve nasıl kullanıldığını ses kayıtları, kısmî çeviri notayazımları ve şematik analizler ile açıklayacağım. Konu hakkında sadece üç örnek üzerinden incelemeye çalıştığım biçimsel yöntemlerin analizinin yüzeysel sonuçlar verdiğinin altını çizmek isterim. Teşhis ettiğim biçimsel yöntemler, geleneksel repertuvardaki eserlerin hepsinde yer almamakla beraber daha kapsamlı bir örneklendirme içeren bir araştırmanın ortaya koyacağı bütün biçimsel yöntemleri de yansıtmayacaktır. Bu makale, “geleneksel repertuvarı geliştiren dutar ustaları, geleneksel saz eseri besteleri yapmak ve geliştirmek için bu biçimsel yöntemleri kullanmıştır” argümanı etrafında şekillenmiş olsa da aynı zamanda makalenin Türkmen müziğine âşinâ olmayan okuyucular için de bir dinleme rehberi olması amaçlanmıştır.

In Turkmenistan, the most common instrument for playing traditional music is the two-string, long-necked lute called dutar. While variants of the dutar and other similar two-string instruments are found in other countries around Central Asia, the Turkmen dutar is noteworthy for its relatively small size and fine, steel strings that allow for high velocity feats of instrumental craftsmanship.

The dutar is the preferred instrument for accompanying bards called bagşy (pl. bagşylar). While I focus here on dutar performance among people who identify as ethnic Turkmen and live in Turkmenistan, the term bagşy or bakshi is also found in northern Iran and Uzbekistan, and such bards claim various ethnic identities and perform in a variety of languages both Turkic and Iranian. The bagşy tradition in Turkmenistan also seems related to other, similar practices such as the zhyrau and aqyn traditions found in Kazakhstan, for example. These include the aşık and ashug traditions practiced by Turks, Armenians, and Azeris in Turkey, Armenia, and Azerbaijan, making it an apt topic for the TUMAC forum.

The bagşy tradition varies regionally around Turkmenistan in terms of performance style, repertoire, and instrumentation in ensemble performances, which sometimes include a spike fiddle called gyjak. In the country’s south-central province of Ahal in particular, a rich repertoire of instrumental compositions for dutar has developed alongside the bagşy repertoire. Instrumental dutar music features highly ornamented melodies that the player strums with a rapid, rarely ceasing series of finger strokes. A shifting melodic line on the lower-pitched of the two strings accompanies the main melody, which is mostly played on the higher-pitched string.

While a number of prominent dutar players have composed new pieces recently enough that their authorship is well-documented, most of the instrumental repertoire is made up of traditional pieces of uncertain authorship. Musicians and other enthusiasts tend to think of these pieces as developing over time as more and more master dutar players gradually add things to them, creating new variations that their followers emulate and seek to preserve.

One feature of such traditional instrumental compositions is that they tend to be highly complex in form. I have not encountered fixed compositional forms such as the peşrev or saz semaisi found in makam-based music, or the 12-bar blues or AABA forms found in jazz standards, for example. Rather, each piece seems to have a unique form, often featuring a linear progression of events. Turkmen instrumental music’s formal complexity may result in part from the tendency for master dutar players to add new ideas to traditional pieces over time, enriching the form of the pieces even as they strive to preserve the interpolations of previous masters.

The repertoire’s often complicated formal structures, along with the unceasing, sometimes blazingly fast manner in which the music is played, can make it fairly inaccessible to unfamiliar listeners. It was not until I began playing the pieces myself that I began to notice some of the logics that seem to have shaped their construction. My aim in this article is to offer a guide to the uninitiated, pointing out a few of the formal patterns I have noticed in the Ahal region’s instrumental dutar repertoire. I do so by analyzing three examples, pointing out a few recurring strategies that dutar masters seem to have employed in the course of composing or enriching them. My hope is that this will help introduce the music to new audiences who might come to appreciate, as I do, the richness of this tradition’s approach to compositional structure.

Case study 1: Goñurbaş mukamy

“Goñurbaş mukamy,” a classic Ahal region instrumental piece, is based on a simple idea: a series of sections progress to higher and higher pitch ranges. A recurring refrain appears after each section. An overview of the sequence of sections and refrains (as commonly played) is provided below. Time markers refer to the corresponding sections of a recording by Çary Taçmammedow:

A [:10-:18 and :31-:39]

Refrain [:19-:28, :39-:50, 1:07-1:19, and 1:38-1:49]

B [:55-1:07]

B’ [1:23-1:38]

C [Taçmammedow skips this section]

D section [1:51-end]

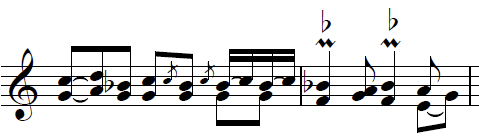

Figure 1. Transcription of a standard way of playing “Goñurbaş Mukamy,” broken into sections. Time markers refer to a recording by Çary Taçmammedow, who plays a few variations not reflected in the transcription. Note Taçmammedow also skips section C in the recording. Notation is transposed according to local convention so that the open strings are [e] and [a]. Transcriptions originally published in Fossum 2010:116-7.

The sections reach progressively higher pitches. What I am calling B’ appears to be a variation of B with an extra measure inserted that descends from a high [g]. The piece builds to something of a climax when the beginning of the C section reaches the highest notes of the dutar. While I won’t provide a transcription of the fourth (D) section here, note that it returns to a lower pitch range, serving as a denouement. Furthermore, the piece modulates here, with the third scale degree rising a half step to create an augmented second interval between the 2nd and 3rd scale degrees. This modal shift in the final section of a piece is one that occurs in a number of pieces in the Turkmen instrumental repertoire.

Most of the instrumental compositions in the dutar repertoire do not feature such an obvious pattern of new sections followed by a recurring refrain. But the general principle of reaching successively higher pitches, often building toward a climax, appears to be a common compositional strategy in the tradition.

Another common strategy appearing in Turkmen compositions is to begin different sections in different ways, but to resolve them in similar ways. We might think of the pattern of following new sections with a recurring refrain in “Goñurbaş mukamy” as one example of this, but the strategy appears here in a more subtle way as well.

Setting aside the refrain, each of the sections I have labeled A, B, B’, and C resolves in the same way before the refrain begins. Interestingly, with each section, more and more material reappears from the resolution of the previous section:

Figure 2. Analysis comparing the final measures of sections A through C of “Goñurbaş mukamy.” Notation is transposed according to local convention so that the open strings are [e] and [a]. Transcription originally published in Fossum 2010.

Thus beyond the recurring refrain that helps tie the piece together, each of the sections A through C includes a similar cadence, repeating material that concluded the section before it.

Case study 2: “Humar ala”

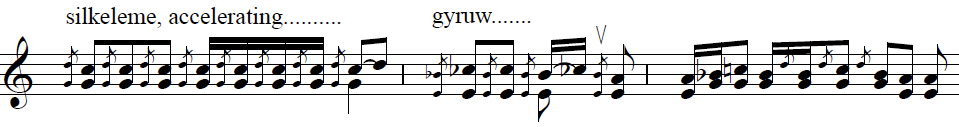

“Humar ala” is a traditional piece most closely associated with the 20th century master Mylly Taçmyradow, who played it so well that later musicians sometimes refused to perform it out of deference. The composition features three basic melodic themes that are reworked as the piece progresses. The three themes, which I will call A, B, and C, are as follows:

A:

B:

C:

Figure 3. Transcription of the three main melodic themes that appear in “Humar ala.” Silkeleme and gyruw refer to strumming techniques. In silkeleme, the dutar player swipes the index finger upward over the strings and then immediately back downward. in gyruw, the thumb and index finger are pinched together and strike downward and immediately back upward. Transcription is transposed so that the open strings are written as [e] and [a]. Originally published in Fossum 2010:120-21.

After these themes are introduced, they appear transposed up a fifth. However, when transposing the tune up a fifth, instead of playing a shifting melodic accompaniment on the lower-pitched of the dutar’s two strings, the dutar player lets the lower-pitched string drone open. This is a common effect in Turkmen music that tends to build intensity. Whereas the tonic of a Turkmen piece—the higher of the two strings strummed open—is usually transcribed as [a], it is common to have portions of a piece that feature a different, temporary tonic. In this case, when the melodic themes are transposed up a fifth, the tonic becomes [e’], an octave up from the droning lower-pitched string [e]. This octave drone tends to create excitement, propelling a piece toward a climax. It is a common feature of a number of pieces in the traditional repertoire.

An overall sketch of “Humar ala,” then, might be as follows, where time markers refer to a recording by Mylly Taçmyradow:

:00-:50 A A B A C C B A (above tonic a)

:51-:57 Transition to tonic e’

:57-1:45 A A B C’ C B C’ C B (above tonic e’)

1:45-1:50 Transition to original tonic

1:51-end A A B A C C B A (above tonic a)

While the sequence of events in the transposed portion of the piece is slightly different from the sequence in the opening portion, most of the melodic material is the same as in the opening and closing of the piece. What I am calling C’ is an abbreviated version of theme C that appears only in the portion of the piece that is transposed up a fifth.

“Humar ala,” like “Goñurbaş mukamy,” builds to a climax in a high pitch range before returning back to a lower pitch range. But where “Goñurbaş mukamy” builds by introducing new sections that ascend to higher pitch ranges, in “Humar ala” recurring ideas are reworked through transposition and repetition in such a way that they build to a climax.

Case study 3: “Döwletyar gyrk”

“Döwletyar gyrk” offers a formally more complex example of Turkmen compositional ideas than either “Humar ala” or “Goñurbaş mukamy” provides. “Döwletyar gyrk” features a series of variations on common themes, modulates up two whole steps, and builds to a climax before returning to thematic material that appears to be related to ideas introduced at the beginning of the piece. I will base my analysis on a recording by Çary Taçmammedow, providing a schematic overview and listening guide (see figure 4 below) rather than a fuller transcription of the piece.

In my hearing of “Döwletyar gyrk,” the piece is structured as three large movements, labeled parts I-III in figure 4. Part I can further be broken into a series of constituent sections, which I label A, B, B’, C, and C’; these appear in the following order: A, B, A, B’, A, C, C’. While the open strings [e] and [a] are the resolution point and center of tonal gravity for the piece as a whole, with a tonic [a], in part II the tonal center modulates upward two whole steps, so that the chord [f#/c#] becomes a temporary tonal center. Part II can also be broken into a series of constituent themes, which I label D1-D4. The modulation back down to the original tonal center marks the beginning of part III, most of which resembles sections C and C’ from part I.

The sections I have labeled B and B’ and C, C’, and C’’ relate to each other, respectively, according to a principle exemplified also in “Goñurbaş mukamy.” These sections begin in unique ways but resolve in similar ways as they descend to the tonic [a].

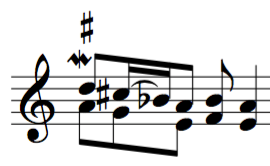

Tying all of these together is a recurring motive I call “motive 1,” which reappears throughout in slightly altered forms (see figure 4). The A sections could be interpreted as a series of closed and open variations of motive 1, the closed variations resolving to the tonic [a] and the open variations alighting on [d] or [e]. Closed variations appear at the beginning and end of the A sections:

Motive 1 reappears in various altered forms throughout the piece. The following variation of motive 1 is incorporated into the resolution of the B sections:

This variation also appears in the C sections. The concluding material of the C sections also includes the following variation of motive 1:

In fact, the C sections could also be interpreted as a made up of a series of fragmented and rhythmically altered variations of motive 1.

Part II of the piece, which modulates upward, is more difficult to analyze as a sequence of variations on a common motive or a series of sections connected by common resolutions.

The main organizing principle of part II appears to be a linear progression toward a climax (3:49-4:01 in the recording). The beginning of part II focuses on establishing the new tonal center [g#/c#] by vamping on it (2:09-2:21) and then a secondary tonal focus [c#/f#] (2:21-2:27). More substantive melodic material (theme D1) begins at 2:27, ascending and descending above the secondary tonal focus [c#/f#]. Beginning at 2:55, a second theme (D2) moves closer to the approaching climax on [a] by altering theme D1’s [g] to a [g#]. Theme D2 is played twice, with the repetitions separated by material recurring from the end of D1. In section D3 (beginning at 3:20), the excitement builds as the melody ascends and descends over a droning, open lower string. The piece reaches its climax in D4 (beginning at 3:49).

Despite its many differences from the part I, part II does feature the following transposed variation of motive 1, appearing in D1 and reappearing between D3 and D4:

After the climactic D4, the piece returns to its original tonal center in what I call part III, beginning at 4:16. In part III, some familiar melodic ideas recur from part I. However, rather than restating sections A and B, part III features new ideas that seem nonetheless related to sections C and C’. The end of what I call C’’ is quite similar to the resolutions of C and C’. Finally, the piece winds down in a coda that serves as a denoument. While the coda seems melodically unrelated to the rest of the piece, it is modally similar and resolves with what could be interpreted as a variation on motive 1 (5:04-5).

Figure 4. Schematic overview of “Döwletyar gyrk.” From Fossum 2010:127.

“Döwletyar gyrk” exhibits a few formal strategies that we also encountered in “Goñurbaş mukamy” and “Humar ala.” In all three cases, melodic ideas or motives that begin a piece are then reused as cadential material that resolves sections. All three might also be understood to have arc-shaped overall contours, with sections ordered such that the pieces progress upward to a climax before returning downward. “Döwletyar gyrk” and “Goñurbaş mukamy” also both feature sections with divergent departures but common returns, beginning in unique ways but resolving in similar ways. And both “Döwletyar gyrk” and “Humar ala” are organized roughly into three parts, with the second part of each piece modulating upward before modulating back to the home tonality in the third part.

Conclusion

While this analysis of three examples from the Turkmen instrumental dutar repertoire offers a sampling of the formal strategies that the tradition’s masters appear to have used in developing these pieces over time, it is not an exhaustive sample. Further analyses of other traditional pieces would reveal formal strategies that these three examples don’t demonstrate, as well as pieces that differ from the ones analyzed here. “Şirin-şeker” and “Yüsüp Öwgan” do not feature arc-shaped contours, for example, beginning in a high range before descending downward to a lower range. Nonetheless, it is my hope that this sampling of three classic pieces from the Ahal region repertoire will give a sense of the formal richness of the music in this tradition.

Notes:

Yorum Bırak